As the internet’s authority on ugly oversized houses, I am frequently asked about my views on tiny houses, mostly by people who hate them.

To get my manifesto started: I love tiny houses with all my heart because, above all, they are a symbol of change.

The tiny house movement is a symbol of moving towards a more sustainable way of life in the wake of the McMansion era of old. It isn’t just smug hipsters moving into tiny houses, it’s everyday people who simply want to live with less. In America, the vehement reaction to the tiny house is to be expected, as Americans love the cleverness of their design and their roguish mission, but at the same time balk at the idea of having less stuff. Of all the editorials against tiny houses, the most common topic of their ire is the thought of tossing out most of their belongings.

However, those who attack the tiny house movement don’t understand that the move to live in smaller dwellings is ultimately a good thing, and that their smug editorials do more harm than good to the cause of living more efficiently, with a smaller environmental footprint.

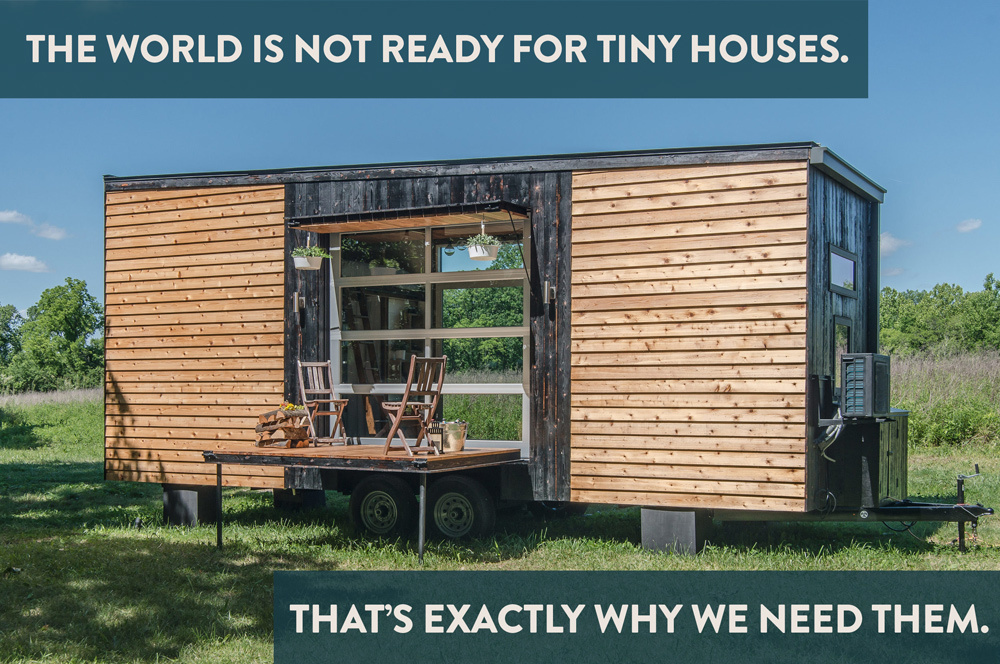

But let’s face it: the world is not yet ready for tiny houses, despite their adoption by ex-McMansion peddler HGTV. The infrastructure of the American housing system is prohibitive of small living in general. Zoning laws with a minimum square footage requirement make many tiny houses illegal to build. Many who have built these houses ended up losing them for this reason alone.

The requirement for tiny houses to be hooked up to municipal utilities makes the idea of mobility all but a pipe dream. Tiny houses are shunned by RV associations mostly because they infringe on their market share, and, as a result, the houses are banned at many campgrounds.

The resistance against living smaller is a systemic one, set in place by the concept of zoning, canonized by the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) at the beginning of the post-war era, and it is only now that these rules are being questioned by the public.

In the US, the FHA subsidized suburban sprawl, and its now-illegal practices of redlining restricted access to loans for those who wanted to purchase housing in the cities. Now that wealth is beginning to enter the cities once more, many cities, most notably New York and San Francisco, are in a crisis of gentrification. If gentrification is the punishment of the cities by outdated FHA policy, the illegality of tiny houses is the punishment of the rural by the same perpetrators.

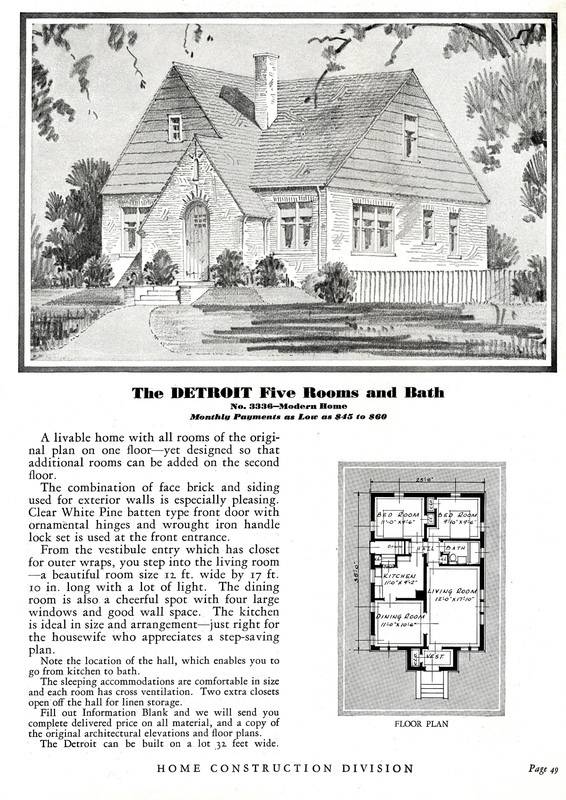

Smug anti-tiny editorials frequently make the assumption that everyone who wants to downsize will go to the extreme of building a 320 square-foot cabin on wheels. In reality, many who are inspired by tiny houses have instead adopted homes of around 1,000 square feet or less. Those who criticize these sizes forget that they are not far off from the small and beloved Minimal Traditional houses of the 20s and 30s. The middle class in America lived tiny after the Great Depression. Is it really a surprise that they wish to do so after the Great Recession as well?

The tiny house represents a generational gap as well. It’s no surprise that many tiny house buyers are young people, who have been accustomed to living in smaller and smaller dwellings in cities because it is all they can afford. The so-called Millennials show a trend of rejecting the isolation of the suburbs to live in cities, and to forego having things in favor of having experiences. These are the children of McMansion owners, who have seen first hand the futility of having to drive fifteen minutes to get to anywhere in particular, and reject the blandness of the suburban landscape, which is infinitely self-replicating in its entirety and gives credence to the pejorative “Anywhere, USA.”

The tiny house reflects also the increasing number of one-person households, and the poor response of home builders to societal shifts in how we live. The fact that home building and the mortgage market caters to the now-changing nuclear family is discussed at length by Dorothea Hayes in the book Redesigning the American Dream: The Future of Housing, Work and Family Life. In her book, Hayes describes how poorly housing markets have reacted to the change in the workforce and how it affects family life. The fact is, more women work, and more people are waiting longer to get married and have children, yet the home builders continue to cater to the “man of the household, his wife, and their two children” paradigm, effectively restricting the availability of housing to those who do not conform to such a lifestyle. Is it such a surprise that, given the lack of homes whose designs cater to the needs of these demographics, that they pursue tiny homes instead? Is it a surprise that those who have been effectively priced out of the housing market pursue houses that they can afford?

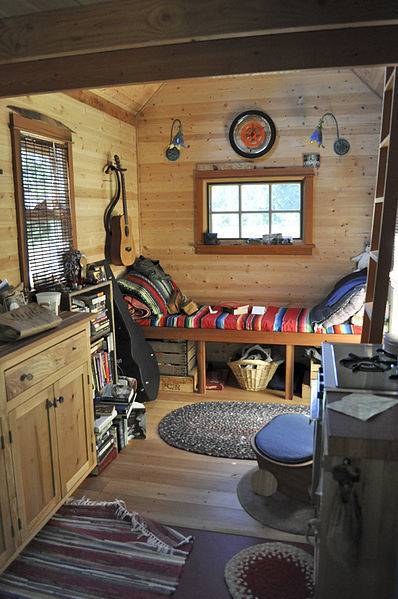

The fact of the matter is, despite the HGTV tiny house zeitgeist, the general public still equates living small with the concept of poverty. However, the craftiness of tiny houses are changing that perception slowly, but surely.

The reason the McMansion dominated the American landscape is because in the post-energy crisis era, Americans equated space with wealth, and could now spend relatively little to build large, if poorly-constructed homes. The small/poor, large/rich dichotomy is starting to fall apart in the era of rejuvenated cities and post-recession skepticism towards the housing market. The isolation brought by having too much space, and the bad taste the recession left in the mouths of young people has led to a total economic rejection of the McMansion and an embrace of the tiny house.

To shift opinions, event slightly, one must first present the population with something radical, and the 320 square-foot cabin on wheels is indeed radical. Perhaps, in the wake of tiny houses, people won’t abandon all of their belongings for a nomadic life, but they may now ask themselves, for the first time since the 80s: “do we really need all of this space?” That, to me, is progress – and progress is good enough.

Kate Wagner is the founder and editor of McMansion Hell, a web site for people who love to hate the ugly houses that became ubiquitous before (and after) the bubble burst. Follow her work here.

Thanks to New Frontier Tiny Homes for the feature image. Photograph by StudioBuell Photography.

People fighting new ideas are almost always moved by deeper motivations (often motivations they won’t admit). Keep speaking your mind Kate, even if it isn’t popular (as if you needed any encouragement :).